| Hurricane Isabel |

We sailed north for 1,200 miles from St Marten in the Caribbean to the

Chesapeake Bay, USA, where “hurricanes hardly happen”, to be

thumped by Isabel, a once in twenty five year phenomena. In our year

of living on Moonshine, our sturdy Westerly Corsair, we’ve

experienced an Atlantic Crossing, two gales, a storm, lots of lightning,

and a hurricane.

Our departure from Puerto Rico was hastened when Topical Storm Ana

came six weeks early, in April. All the way north through the British

and US Virgins, and the Bahamas we had muttered, “June too soon.

July standby. August you must. September remember. October all

over.” We motor sailed up the ICW from West Palm Beach to Norfolk

and into the Chesapeake Bay. In July we’d stood fast as the remnants

of Tropical Storm Claudette bashed about us. At the beginning of

September we took shelter in a lightening storm in Solomons Island,

Maryland, one hour south of Washingon D.C. We had anticipated

completing our end of first year sort-out-fix-it in Annapolis, three days

sail away. We found the Solomons suited all our needs, and was

cheaper. One week after our arrival on 7th September tropical storm

Isabel grew to hurricane strength. By the 11th she was a category five

with 155 mile an hour winds.

Sunday 14th September: Hurricane Isabel was north of the Bahamas

heading towards us in the U.S.. She was still category five but,

weakening. We were amazed. Isabel was forecast to track above the

usual points of landfall such as the Bahamas, Florida and South

Carolina, to hit Moonshine in Maryland on Thursday 18th September in

the afternoon. Wednesday we were flying home for a visit, not.

Moonshine was to have been berthed in the Hospitality Harbour whilst

we visited the UK.

Three anchors in a protected area? Versus secured in a spider web of

lines on a dock? Would the anchors hold? How to configure the lines?

Would we be able to stay? We knew of one marina in the south which

ordered all boats out during hurricanes. In February St Margarets

doubled Moonshine’s insurance premium and reduced the cover, no

longer insuring against damage caused by named storms even if we

were out of the designated hurricane belt, (north of Cape Hatteras,

North Carolina and south of Grenada). Searches for alternatives offered

no better for new clients.

Monday 15th September: Isabel had reduced speed to category four.

With a $200 fee to change each ticket, I argued with British Airways

that we, Brits, were not “choosing” , but, being forced to change our

flights because our home was in danger. My “special circumstances”

was met by supervisors quoting “policy. We decided to wait until

Tuesday for a BA thaw. The genoa, the main and the sail bag were

removed. Most of D dock were in “denial“. Dave on Island Girl changed

the oil.

Tuesday 16th September: John walked the dock and made the first

attempt on the spider’s web of lines which would be Moonshine’s

safety net. Fighter jets flew out of the Naval Air Warfare Centre

(NAWCAD) five miles away, to airbases out of Isabel’s path. Ships in

the US naval fleet sailed out from Norfolk, Virginia, to the safety of the

Atlantic ocean. British Airways relaxed their policy for those flying on

Thursday and Friday. But, it was no way from BA for us. Spitting we

paid out the $200 each.

The tensions grew. Our usually healthy appetites died. Diet coke kept

us going. Bill Glascock has owned the Hospitality marina, our chosen

Hurricane hole , for seventeen years. Isobel was his first hurricane.

Whilst fielding anxious questions he emptied his floating, wooden

office of electrical equipment and placed giant fenders between it and

the dock. Greg von Ziclinski and Bill had been friends since high

school. Greg lives aboard a lifeboat from a naval warship, converted for

his “ocean ministry“, “2God.org”. I nick named him Spiderman. Greg

used to import yachts. His knowledge and advice on knots and spider

web strategy were invaluable.

The dock was full of discussions on the weather channel’s latest and

the perfect cats cradle. Trawlers, motor boats and yacht skippers

compared knots. The clove hitch with two half hitches was deemed

best. If it wasn’t knots it was second guessing the height of the surge,

the seawater which the strong winds would pile up ashore. If the lines

were not tied tightly enough at the top of the pilings the surge could

float the boat off free to smash itself on pilings and neighbours. One

of the empty berths next to us belonged to “Best Pals.” Like numerous

keel-less motor boats it had been lifted out then, blocked one foot off

the ground about two hundred yards inland. Another power boater

wondered if a flimsy tarpaulin would help keep his seats dry. He

wrapped his four puny lines, cracked open a beer and lumbered off.

Perhaps, clueless was better than the gnawing threat we felt. Perhaps

not.

John spent the night following Isabel’s relentless flight on the NOAA,

(National Oceanic graphic and Atmospheric Administration) website

and researching the best spiderweb configuration. Across the dock

Island Girl, a Cape Dory 37 were strung out. The boat is Dave and Cindy

Foss’s only home. After seven years of planning they set out in July

from Michigan, in the northern US. Dave’s mother-in-law was dead

against cruising. Her name? Isabel.

The joke went round that the Floridians had put out huge fans to blow

Isabel north. It was working. Again, we chewed over whether to stay

on the dock or head for a creek. Local knowledge suggested St

Leonard’s Creek where the high sides gave good protection. The

berths either side of Moonshine were free. We gave black looks to

those entering the D dock channel. In the adjacent, Spring Cove

Marina the boats were crammed in.

As with the discussions on spider webs, so with the anchor debates.

Danforths were considered best for the mud of the Chesapeake. Some

dismissed the Bahamian moor V formation because the boat can twist

in the wind, winding the two chains around each other. If one knew

the wind direction, two anchors on the same side could pull against it,

however, this is risky as the final track of the hurricane is

unpredictable. The triangle method was considered best. Whether at

anchor or on a dock everyone viewed other people’s boats as

potential liabilities. In their mid twenties Dan and Carol on Alona, an

ancient trawler, had been anchored in St Leonard’s Creek for two days

when older cruisers set their one (!) anchor over Alona’s anchor line,

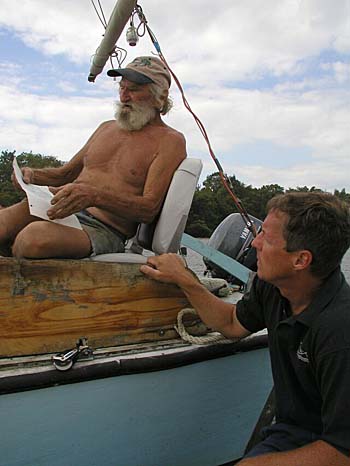

and refused to move it. Alona were forced to re-set. Eighty three year

old Captain Seaweed (think Ben Gun) plumbed the depth of the

furthest end of Cuckold Creek. Using a triangular configuration of

three anchors he wedged his steel boat with its four foot draft into a

nook. He had a fourth anchor spare in case. Solomons Island is on the

Patuxent River along which there are dozens of creeks offering

hurricane holes. Trooper, a Hillyard 37 were unsure about the dock

they were offered in Mill Creek. They dropped a lead line and

discovered a Hillyard 37 size hurricane hole. Three anchors and a web

of twenty lines, some over one hundred feet long reaching to the dock

and surrounding trees, ensured that the only movement could be six

inches down into the mud below. In June in Pipeline Canal near

Southport, North Carolina, during a vicious lightning storm, we

dragged, for the first time, onto a beach and bent our CQR. It knocked

our confidence and swayed our decision to stay on the dock.

Wednesday 17th. The “fear of the unknown” gripped dock masters and

cruisers. Isabel was now category two with winds of 110mph at the

eye wall. Sleep was fitful and disturbing. Two am John could not sleep.

The thumping noises on the cabin roof turned out to be John taking

the barbecue and the life raft off the stern railings and the wind

generator from the gantry, removing all items that added windage.

The bimini was dismantled. The spray hood strapped down. Even the

pegs from the clothes line. The fishing rods, boat hook, brush and

danboy were stored in the forward cabin with the bimini canvas, sail

bag and sails. The mainsail battens lay on the salon sole. The outboard

motor, horse shoe life preserver, empty jerry cans for water and fuel

joined the wind vane in Moonshine’s cavernous cockpit locker.

Fenders were hung around Moonshine’s bow and aft. The governors of

North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland and Delaware declared states of

emergency and mobilized the national guard. West Marine and other

shops were boarded up.

Still no one came to secure the 40 foot Beneteau next to us. Bill and

Greg worked tirelessly securing boats abandoned by their owners. It

seemed surreal to see them tying a rope rail lifeline along the walkway

on a sunny day with blue cloudless skies. Moonshine sat in her web:

sixteen 5/8th of an inch dock lines attached to eleven pilings; her 45lb

CQR set on chain just off her bow and her spare anchor rode wrapped

around the windlass then, tied off 100 feet away to a pile on the other

side of the channel. Would the cleats hold? The preparations kept the

stress at bay. John extended the web around the Beneteau. The

owner’s dockside tub of roses was lugged into the Beneteau’s cockpit.

The intention to stay onboard Moonshine during the storm seemed

foolhardy, a room, in the hotel overlooking the boats was the answer.

We cut the cost by sharing with Island Girl.

Thursday 19th. At five am we tied Moonbeam, the dinghy, on a

diagonal between two piles. If she was blown anywhere it would be

into the mud around the edge of the mini cove. The sky was grey.

High tide at 9am did not go down. Grim predictions filled the paper.

The batteries to power the bilges were charged by running the

engine. US boats detached the shore power. The lines from the

windlass stretched across the channel were raised thereby allowing

skippers to haul their boats away from dock. No more boats could

enter C or D docks. It was blustery and spitting. We checked into the

hotel with a marina cart full of waterproofs, torches, cameras, laptops,

picnics, and our most important possessions. The weather channel

remained on until the power failed later that night.

Isabel made land fall in Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina at 11am. (See

photograph of television coverage.) Cars were turned upside down in

the nine foot storm surge. The Outer Banks and North Carolina coast

took the full force. Houses were swamped and some washed away in

nearby Kitty Hawk. It was estimated that 300,000 were without power

in Virginia Beach. We thought of our friends in Belhaven North

Carolina, where the waters from Pamlico Sound, just inside the Outer

Banks would flood the town, just as it did during Floyd in 1999. Floyd

hit less populated areas after a drought. Isabel was aiming for

metropolitan areas such as Norfolk, Annapolis, Washington DC and

Baltimore after a rainy summer.

We experienced the first effects of the bands (or spirals) of the

system along the Patuxent River at 5 pm. Isabel’s now increasing

speed meant there was less rain fall. The water had risen four feet and

lapped at the base of the finger pontoons, just under the walkway.

John and the other skippers raised the lines even further up the

pilings. By the time the winds reached Solomons Island they were

down to a mere sustained 40 knots with gusts of storm force 11, not

the estimated 74 knots, hurricane strength. By the 7.30pm the winds

lulled. This gave us a false sense of security. We thought we’d got

away with it. Replete from the our Chinese take away we watched the

boats from our fifth floor hotel room. Suddenly Dave’s cap was blown

across the room. 9.30pm The winds had returned with a vengeance -

up by 20 knots. We were now in the north east quadrant (or RFQ, right

front quadrant) where the winds are at their highest, and the surge

highest. All hell broke loose. We hadn’t got away with it at all. The

eye wall was coming.

On the fifth floor the windows shook. Huge trees arched and crashed.

Below the masts tilted at an acute angle. The rigging screamed. We

recalled our first days out in the Atlantic, two hundred miles off

shore, in a 40 knot storm with gusts of 55. At least this time we were

up a dog leg, at the back of Back Creek, protected by trees and a large

hotel. Back into his soggy waterproofs John found a far more menacing

situation. The extra twenty knots felt like forty. With the darkness

and rain obscuring their vision the skippers used the rope rail along

the walkway to pull themselves against the wind, through the waves

washing over the dock which was now two feet deep under water.

Strangely it was 70 degrees, quite warm. There were several

explosions and flashes in the distance. The sky turned green. The

town’s power transponders had blown. The boat’s lines on D dock

were secure. It was way too hazardous for any more changes to be

made. Reluctant and feeling helpless in the face of such severe

conditions John and Dave returned to the hotel warning other

skippers not to go out.

Isabel stomped north to Annapolis at the top of the Chesapeake Bay

causing extensive flooding and wind damage.

Friday 19th September: 4.00am The winds were abating. The dock was

still two feet under water. Nonetheless all was well in Hospitality

Harbour. Our new D-dock family had survived remarkably intact.

8am It was a beautiful morning with clear blue skies, and hardly a

breath of wind. We sloshed along the dock. Moonshine floated above

us. We motored with the “vicar”, Greg, a mile down Back Creek to the

opening into the Patuxent River where the damage was heaviest. The

front line of onslaught from Isabel left pilings stripped of their

walkways and docks broken up. The bow sprit of a Cabo Roca had

been smashed against its pilings. The port side hull of a Swan 42 was

splintered and completely separated at the hull deck join. A chilling

site. Shredded sails flapped in the light breeze.

In Spring Cove Marina, the marina next to us, a boom had torn through

a bimini. Their Autumn Newsletter seemed ironic, “If everyone is

prepared, I’m sure the hurricane will miss!” The power was still out.

The marina shop fridge was de-frosting. Cruisers slurped free, melting

ice cream. Several metal strips in the roof of the large boat ‘garage”

had been ripped up. Nails in the sheet had gouged holes in a sleek

motor boats gel coat. Captain Seaweed motored past, wrinkled and

toothless, as ever, his sixth hurricane under his keel with no ill

effects. Alona were re-anchored near the picturesque Drum Point

Lighthouse, Dan and Carol were re-attaching their makeshift red check

tablecloth-awning. In St Leonard’s Creek a massive oak had fallen

towards Alona … it had landed on her lines.

By 4pm the water was under the dock. Bill re-activated the power. Air

conditioning flowed into the trawlers. We were able to climb up to

Moonshine, still high in the water. It was good to be back on our home.

The Beneteau’s owner never showed. The rose bush was a bit the

worse for hurricane wear. The reparations took a day, much faster

than the fearful preparations. The D dockers celebrated with Bill and

Greg in Solomons Island Yacht Club, before a D-Day barbecue.

Island Girl is going to make it to the Islands. We’re now ready for fair

winds as we head south to the Bahamas, Cuba, the Caribbean and the

San Blas.

Text copyright Nicola Rodriguez Oct 2003

Photographs copyright John & Nicola Rodriguez Oct 2003

Chesapeake Bay, USA, where “hurricanes hardly happen”, to be

thumped by Isabel, a once in twenty five year phenomena. In our year

of living on Moonshine, our sturdy Westerly Corsair, we’ve

experienced an Atlantic Crossing, two gales, a storm, lots of lightning,

and a hurricane.

Our departure from Puerto Rico was hastened when Topical Storm Ana

came six weeks early, in April. All the way north through the British

and US Virgins, and the Bahamas we had muttered, “June too soon.

July standby. August you must. September remember. October all

over.” We motor sailed up the ICW from West Palm Beach to Norfolk

and into the Chesapeake Bay. In July we’d stood fast as the remnants

of Tropical Storm Claudette bashed about us. At the beginning of

September we took shelter in a lightening storm in Solomons Island,

Maryland, one hour south of Washingon D.C. We had anticipated

completing our end of first year sort-out-fix-it in Annapolis, three days

sail away. We found the Solomons suited all our needs, and was

cheaper. One week after our arrival on 7th September tropical storm

Isabel grew to hurricane strength. By the 11th she was a category five

with 155 mile an hour winds.

Sunday 14th September: Hurricane Isabel was north of the Bahamas

heading towards us in the U.S.. She was still category five but,

weakening. We were amazed. Isabel was forecast to track above the

usual points of landfall such as the Bahamas, Florida and South

Carolina, to hit Moonshine in Maryland on Thursday 18th September in

the afternoon. Wednesday we were flying home for a visit, not.

Moonshine was to have been berthed in the Hospitality Harbour whilst

we visited the UK.

Three anchors in a protected area? Versus secured in a spider web of

lines on a dock? Would the anchors hold? How to configure the lines?

Would we be able to stay? We knew of one marina in the south which

ordered all boats out during hurricanes. In February St Margarets

doubled Moonshine’s insurance premium and reduced the cover, no

longer insuring against damage caused by named storms even if we

were out of the designated hurricane belt, (north of Cape Hatteras,

North Carolina and south of Grenada). Searches for alternatives offered

no better for new clients.

Monday 15th September: Isabel had reduced speed to category four.

With a $200 fee to change each ticket, I argued with British Airways

that we, Brits, were not “choosing” , but, being forced to change our

flights because our home was in danger. My “special circumstances”

was met by supervisors quoting “policy. We decided to wait until

Tuesday for a BA thaw. The genoa, the main and the sail bag were

removed. Most of D dock were in “denial“. Dave on Island Girl changed

the oil.

Tuesday 16th September: John walked the dock and made the first

attempt on the spider’s web of lines which would be Moonshine’s

safety net. Fighter jets flew out of the Naval Air Warfare Centre

(NAWCAD) five miles away, to airbases out of Isabel’s path. Ships in

the US naval fleet sailed out from Norfolk, Virginia, to the safety of the

Atlantic ocean. British Airways relaxed their policy for those flying on

Thursday and Friday. But, it was no way from BA for us. Spitting we

paid out the $200 each.

The tensions grew. Our usually healthy appetites died. Diet coke kept

us going. Bill Glascock has owned the Hospitality marina, our chosen

Hurricane hole , for seventeen years. Isobel was his first hurricane.

Whilst fielding anxious questions he emptied his floating, wooden

office of electrical equipment and placed giant fenders between it and

the dock. Greg von Ziclinski and Bill had been friends since high

school. Greg lives aboard a lifeboat from a naval warship, converted for

his “ocean ministry“, “2God.org”. I nick named him Spiderman. Greg

used to import yachts. His knowledge and advice on knots and spider

web strategy were invaluable.

The dock was full of discussions on the weather channel’s latest and

the perfect cats cradle. Trawlers, motor boats and yacht skippers

compared knots. The clove hitch with two half hitches was deemed

best. If it wasn’t knots it was second guessing the height of the surge,

the seawater which the strong winds would pile up ashore. If the lines

were not tied tightly enough at the top of the pilings the surge could

float the boat off free to smash itself on pilings and neighbours. One

of the empty berths next to us belonged to “Best Pals.” Like numerous

keel-less motor boats it had been lifted out then, blocked one foot off

the ground about two hundred yards inland. Another power boater

wondered if a flimsy tarpaulin would help keep his seats dry. He

wrapped his four puny lines, cracked open a beer and lumbered off.

Perhaps, clueless was better than the gnawing threat we felt. Perhaps

not.

John spent the night following Isabel’s relentless flight on the NOAA,

(National Oceanic graphic and Atmospheric Administration) website

and researching the best spiderweb configuration. Across the dock

Island Girl, a Cape Dory 37 were strung out. The boat is Dave and Cindy

Foss’s only home. After seven years of planning they set out in July

from Michigan, in the northern US. Dave’s mother-in-law was dead

against cruising. Her name? Isabel.

The joke went round that the Floridians had put out huge fans to blow

Isabel north. It was working. Again, we chewed over whether to stay

on the dock or head for a creek. Local knowledge suggested St

Leonard’s Creek where the high sides gave good protection. The

berths either side of Moonshine were free. We gave black looks to

those entering the D dock channel. In the adjacent, Spring Cove

Marina the boats were crammed in.

As with the discussions on spider webs, so with the anchor debates.

Danforths were considered best for the mud of the Chesapeake. Some

dismissed the Bahamian moor V formation because the boat can twist

in the wind, winding the two chains around each other. If one knew

the wind direction, two anchors on the same side could pull against it,

however, this is risky as the final track of the hurricane is

unpredictable. The triangle method was considered best. Whether at

anchor or on a dock everyone viewed other people’s boats as

potential liabilities. In their mid twenties Dan and Carol on Alona, an

ancient trawler, had been anchored in St Leonard’s Creek for two days

when older cruisers set their one (!) anchor over Alona’s anchor line,

and refused to move it. Alona were forced to re-set. Eighty three year

old Captain Seaweed (think Ben Gun) plumbed the depth of the

furthest end of Cuckold Creek. Using a triangular configuration of

three anchors he wedged his steel boat with its four foot draft into a

nook. He had a fourth anchor spare in case. Solomons Island is on the

Patuxent River along which there are dozens of creeks offering

hurricane holes. Trooper, a Hillyard 37 were unsure about the dock

they were offered in Mill Creek. They dropped a lead line and

discovered a Hillyard 37 size hurricane hole. Three anchors and a web

of twenty lines, some over one hundred feet long reaching to the dock

and surrounding trees, ensured that the only movement could be six

inches down into the mud below. In June in Pipeline Canal near

Southport, North Carolina, during a vicious lightning storm, we

dragged, for the first time, onto a beach and bent our CQR. It knocked

our confidence and swayed our decision to stay on the dock.

Wednesday 17th. The “fear of the unknown” gripped dock masters and

cruisers. Isabel was now category two with winds of 110mph at the

eye wall. Sleep was fitful and disturbing. Two am John could not sleep.

The thumping noises on the cabin roof turned out to be John taking

the barbecue and the life raft off the stern railings and the wind

generator from the gantry, removing all items that added windage.

The bimini was dismantled. The spray hood strapped down. Even the

pegs from the clothes line. The fishing rods, boat hook, brush and

danboy were stored in the forward cabin with the bimini canvas, sail

bag and sails. The mainsail battens lay on the salon sole. The outboard

motor, horse shoe life preserver, empty jerry cans for water and fuel

joined the wind vane in Moonshine’s cavernous cockpit locker.

Fenders were hung around Moonshine’s bow and aft. The governors of

North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland and Delaware declared states of

emergency and mobilized the national guard. West Marine and other

shops were boarded up.

Still no one came to secure the 40 foot Beneteau next to us. Bill and

Greg worked tirelessly securing boats abandoned by their owners. It

seemed surreal to see them tying a rope rail lifeline along the walkway

on a sunny day with blue cloudless skies. Moonshine sat in her web:

sixteen 5/8th of an inch dock lines attached to eleven pilings; her 45lb

CQR set on chain just off her bow and her spare anchor rode wrapped

around the windlass then, tied off 100 feet away to a pile on the other

side of the channel. Would the cleats hold? The preparations kept the

stress at bay. John extended the web around the Beneteau. The

owner’s dockside tub of roses was lugged into the Beneteau’s cockpit.

The intention to stay onboard Moonshine during the storm seemed

foolhardy, a room, in the hotel overlooking the boats was the answer.

We cut the cost by sharing with Island Girl.

Thursday 19th. At five am we tied Moonbeam, the dinghy, on a

diagonal between two piles. If she was blown anywhere it would be

into the mud around the edge of the mini cove. The sky was grey.

High tide at 9am did not go down. Grim predictions filled the paper.

The batteries to power the bilges were charged by running the

engine. US boats detached the shore power. The lines from the

windlass stretched across the channel were raised thereby allowing

skippers to haul their boats away from dock. No more boats could

enter C or D docks. It was blustery and spitting. We checked into the

hotel with a marina cart full of waterproofs, torches, cameras, laptops,

picnics, and our most important possessions. The weather channel

remained on until the power failed later that night.

Isabel made land fall in Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina at 11am. (See

photograph of television coverage.) Cars were turned upside down in

the nine foot storm surge. The Outer Banks and North Carolina coast

took the full force. Houses were swamped and some washed away in

nearby Kitty Hawk. It was estimated that 300,000 were without power

in Virginia Beach. We thought of our friends in Belhaven North

Carolina, where the waters from Pamlico Sound, just inside the Outer

Banks would flood the town, just as it did during Floyd in 1999. Floyd

hit less populated areas after a drought. Isabel was aiming for

metropolitan areas such as Norfolk, Annapolis, Washington DC and

Baltimore after a rainy summer.

We experienced the first effects of the bands (or spirals) of the

system along the Patuxent River at 5 pm. Isabel’s now increasing

speed meant there was less rain fall. The water had risen four feet and

lapped at the base of the finger pontoons, just under the walkway.

John and the other skippers raised the lines even further up the

pilings. By the time the winds reached Solomons Island they were

down to a mere sustained 40 knots with gusts of storm force 11, not

the estimated 74 knots, hurricane strength. By the 7.30pm the winds

lulled. This gave us a false sense of security. We thought we’d got

away with it. Replete from the our Chinese take away we watched the

boats from our fifth floor hotel room. Suddenly Dave’s cap was blown

across the room. 9.30pm The winds had returned with a vengeance -

up by 20 knots. We were now in the north east quadrant (or RFQ, right

front quadrant) where the winds are at their highest, and the surge

highest. All hell broke loose. We hadn’t got away with it at all. The

eye wall was coming.

On the fifth floor the windows shook. Huge trees arched and crashed.

Below the masts tilted at an acute angle. The rigging screamed. We

recalled our first days out in the Atlantic, two hundred miles off

shore, in a 40 knot storm with gusts of 55. At least this time we were

up a dog leg, at the back of Back Creek, protected by trees and a large

hotel. Back into his soggy waterproofs John found a far more menacing

situation. The extra twenty knots felt like forty. With the darkness

and rain obscuring their vision the skippers used the rope rail along

the walkway to pull themselves against the wind, through the waves

washing over the dock which was now two feet deep under water.

Strangely it was 70 degrees, quite warm. There were several

explosions and flashes in the distance. The sky turned green. The

town’s power transponders had blown. The boat’s lines on D dock

were secure. It was way too hazardous for any more changes to be

made. Reluctant and feeling helpless in the face of such severe

conditions John and Dave returned to the hotel warning other

skippers not to go out.

Isabel stomped north to Annapolis at the top of the Chesapeake Bay

causing extensive flooding and wind damage.

Friday 19th September: 4.00am The winds were abating. The dock was

still two feet under water. Nonetheless all was well in Hospitality

Harbour. Our new D-dock family had survived remarkably intact.

8am It was a beautiful morning with clear blue skies, and hardly a

breath of wind. We sloshed along the dock. Moonshine floated above

us. We motored with the “vicar”, Greg, a mile down Back Creek to the

opening into the Patuxent River where the damage was heaviest. The

front line of onslaught from Isabel left pilings stripped of their

walkways and docks broken up. The bow sprit of a Cabo Roca had

been smashed against its pilings. The port side hull of a Swan 42 was

splintered and completely separated at the hull deck join. A chilling

site. Shredded sails flapped in the light breeze.

In Spring Cove Marina, the marina next to us, a boom had torn through

a bimini. Their Autumn Newsletter seemed ironic, “If everyone is

prepared, I’m sure the hurricane will miss!” The power was still out.

The marina shop fridge was de-frosting. Cruisers slurped free, melting

ice cream. Several metal strips in the roof of the large boat ‘garage”

had been ripped up. Nails in the sheet had gouged holes in a sleek

motor boats gel coat. Captain Seaweed motored past, wrinkled and

toothless, as ever, his sixth hurricane under his keel with no ill

effects. Alona were re-anchored near the picturesque Drum Point

Lighthouse, Dan and Carol were re-attaching their makeshift red check

tablecloth-awning. In St Leonard’s Creek a massive oak had fallen

towards Alona … it had landed on her lines.

By 4pm the water was under the dock. Bill re-activated the power. Air

conditioning flowed into the trawlers. We were able to climb up to

Moonshine, still high in the water. It was good to be back on our home.

The Beneteau’s owner never showed. The rose bush was a bit the

worse for hurricane wear. The reparations took a day, much faster

than the fearful preparations. The D dockers celebrated with Bill and

Greg in Solomons Island Yacht Club, before a D-Day barbecue.

Island Girl is going to make it to the Islands. We’re now ready for fair

winds as we head south to the Bahamas, Cuba, the Caribbean and the

San Blas.

Text copyright Nicola Rodriguez Oct 2003

Photographs copyright John & Nicola Rodriguez Oct 2003